Background: This past weekend (April 6-7) was a preaching weekend for me at Christ Church Easton. The lectionary Gospel reading was John 20:19-31, which is popularly referred to as the “Doubting Thomas” story. I also preached on this passage last year and wanted to make sure to take it in a new direction. I am grateful especially to Debie Thomas and her book, “A Faith of Many Rooms,” which is quoted and referred to.

“Doubt and Faith“

It’s today’s reading where our friend Thomas earns the nickname that history and culture gave him: “Doubting Thomas.” And we are told not to be a Doubting Thomas.

I want to discuss whether doubt is a bad thing and whether in Thomas’s shoes, any of us might not do the same thing.

This is not the first time we meet Thomas in John’s Gospel. The first story he is a part of is the raising of Lazarus.

Mary and Martha send a message to Jesus that their brother Lazarus is sick, hoping that Jesus will come to heal him. Jesus famously waits a couple days before going to see them. And when he’s ready, he says to his disciples, “Let us go back to Judea.”

They know there are people in Judea who already want to stone and kill Jesus. Going back to Judea is exactly what they don’t want to do. They try to hash out whether this is a good idea and Jesus says, “Lazarus is dead, let us go to him.”

This is where Thomas pipes up and says to the group, “Let us also go, that we may die with him.”

If Lazarus is dead, and Jesus is walking straight into the storm and facing death head on, Thomas says, alright gang, let’s go die with him.

And off they go. Thomas has no fear and no problem going to die with and for Jesus.

Fast forward through John’s Gospel: there is the raising of Lazarus, Jesus’s entrance into Jerusalem, then his betrayal, arrest, and crucifixion. Now the disciples are caught up in uncertainty, grief, and the lost feeling of what was going to happen now.

The story of the empty tomb, of Mary Magdalene meeting the risen Jesus there that we just heard last weekend on Easter, has just happened. It is evening on that same day, the first day of the week, and the disciples are locked in a room fearing the same fate that Jesus met might be waiting for them at the hands of the Jews.

Jesus appears to the disciples. This incredible experience. But Thomas isn’t there. He gets back after the fact. And the disciples all tell him, “We’ve seen the Lord,” he was here with us.

Thomas says, unless I see it for myself, unless I see HIM for myself, I will not believe.

Author Debie Thomas was born in India. Her father was a Christian minister there and their culture has a special relationship with the apostle Thomas.

In her new book, “A Faith of Many Rooms,” which we’ll have a few small groups reading and discussing, she has this to say about Thomas and his doubt:

“Cautious. Skeptical. Stubborn. Daring.”

“A man who yearned for a living encounter with Jesus—an encounter of his own, unmediated by the claims and assumptions of others. A man who wouldn’t settle for hand-me-down religion but demanded a firsthand experience of God to anchor and enliven his faith. To me, this speaks not only to Thomas’s integrity but to his hunger. His desire. His investment. He wasn’t spiritually passive. He didn’t want the outer trappings of religion if he couldn’t know its fiery core. He was alive with his longing.”

I don’t know about you, but I have never been able to just accept something that people tell me without finding out for myself. This didn’t make for an easy job for my parents. They came home once when I was 9 or 10 years old, to find me stuck in the mud in the middle of the creek behind our house at low tide. I didn’t think I would get stuck, despite people warning me. My mom’s boots are still at the bottom of the creek there.

Another time, my mom had to come extract me from the clay they dredged out of Town Creek in Oxford, which I walked into–waist-deep to see how far I could get.

As a teenager spelunking in John Brown’s Cave in Harpers Ferry, in the pitch black with headlamps, a friend and I climbed up a wall about 20 feet to see what it was like. It took a minor miracle for us to make our way back down.

I grew up in the Episcopal Church, I was baptized and confirmed at Holy Trinity Church in Oxford, I attended St. James Episcopal School in Hagerstown for a time. As I got older, I kept at the periphery of church, I appreciated the teachings, I liked what this Jesus guy was all about, but I couldn’t make the leap from interested to invested.

I think I have always been Thomas when it comes to faith. I needed my own experience.

How does that happen? How do we find that kind of experience?

Let’s look at something that happens right after Thomas says he won’t believe unless he sees for himself.

After Thomas says he’s not on board, John writes: “A week later… his disciples were in the house again and Thomas was with them.”

A week has gone by, and Thomas is still there.

What does that tell us about Thomas? Even though he wasn’t ready to believe, even though he didn’t have the experience that the others had, he didn’t quit. He didn’t hang it up. He kept showing up. He was willing to give it time when he himself wasn’t feeling it.

What does it say about the disciples? They didn’t shun him. They didn’t ostracize him. They stood by their experience, they trusted Jesus, and they loved Thomas. They were willing to let things work themselves out.

Life goes on. The disciples stay together. Thomas keeps working through things. And a week later, Jesus comes back and gives Thomas the exact thing he asked for.

What do we learn about Jesus? He gives Thomas the experience that he needs to believe. He meets Thomas where he was and gives him his hands and shows him his side and says, “Do not doubt, but believe.” Thomas, man of his word, says, “My Lord and my God.” He believes.

What does that mean for Thomas? What does it mean for us to believe?

Here’s the thing about belief when it comes to faith. It sounds nice, it sounds reassuring: if you believe, you’re all set. If you believe, you’ll have eternal life. So how do we as Christians today show our belief? We go to church, meaning worship services. We take Communion. Maybe we wear a cross around our necks. If we’re on social media and someone says, “bet you won’t post the Lord’s Prayer,” we say, oh yeah, watch this… and post it… Hhhmm… that’ll show them.

I subscribe to the idea that if you want to know what someone believes, watch their actions. I think that’s what Jesus was and is banking on as well. If you want to know what the disciples did after their encounters with the risen Christ, go take a look in the Book of Acts. They risked their lives, they met in houses and walked and sailed hundreds of miles to win new followers of Christ. If that was a part of belonging to a church today, I think we’d all be in a bit of trouble.

One person whose journey isn’t outlined specifically in Acts is Thomas’s. Scholarship points to the idea that Thomas is who took Christianity to India. They have statues of him and monasteries and they hold that their Christian roots go all the way back to one of Jesus’s first disciples. A lot further than our roots in the United States go.

Debie Thomas outlines different stories that are associated with the apostle Thomas in India: the pared down version goes like this.

Thomas sailed to Kerala in 52 CE, so about 20 years after Jesus’s death, resurrection, and ascension–20 years after Thomas’s encounter with the risen Christ. He wanted to preach to the Jewish colonies that were settled near Cochin.

He was very successful, converting both Jews and Brahmins and he followed the coastline south, winning hundreds of new followers and believers of Jesus and establishing seven churches along the waterways of Kerala. He crossed over the land to the east coast near Madras.

He was so successful as a preacher and a community builder that he made the devout Brahmins in the region jealous and angry and they speared him to death in 72 CE.

For 20 years, Thomas worked with the other disciples around Jerusalem and the Middle East spreading the good news of Jesus. And for the next 20 years after that, he went to strange lands where he didn’t speak the language, where he was an outsider, where it was Thomas and the Holy Spirit and the communities of believers he helped build. Right up until the religious authorities killed him for it.

The apostle Thomas’s actions show how deeply he believed.

Debie Thomas asks this question: “What if doubt itself can be a testimony?”

She says, “If nothing else, Thomas assures me that the business of the good news–of accepting it, of living it out, and of sharing it with the world–is tough. It’s okay to waver. It’s okay to take our time. It’s okay to probe, prod, and insist on more… I need Thomas–doubter and disciple, agnostic and apostle–to show me what faith truly is.”

His doubt is honest. It is heartfelt. It is a part of who he was and part of the process of who he was becoming. Maybe you can see yourself in Thomas. Maybe doubt and questions are a part of your faith journey. They are still a part of mine. God can use our doubt as a starting point or to lead us further down the path he has laid out for us. As long as we don’t give up.

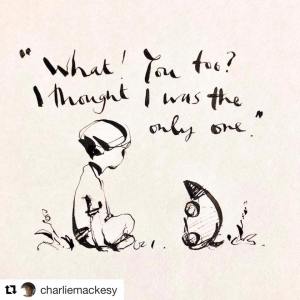

I wonder about Thomas and what his style of evangelism would have been. I picture him having a meal with a group of people who are eagerly listening to what he has to say. Except for one person sitting at the end of the table who has a raised eyebrow, shaking his or her head. Slow to accept, skeptical to believe.

I see Thomas smile, laugh a little, and say, “You’ve got doubts, huh? Me, too. Let me tell you a story about doubts and how they can be a part of faith.”